Music by DANIEL DORFF |

|

| Article about Daniel Dorff in Fanfare Magazine July/August 2013 by Peter Burwasser |

|

|

These

are not the words of some naïve wunderkind. Composer Daniel Dorff's

grasp of musical history is as sophisticated as can be. Even in this era

of grand musical eclecticism, Dorff has been exposed, at a very close

level, to an extraordinary diversity of styles and approaches to his art

form. A formative period in his career occurred in graduate school, in

the late 1970s, where he studied with the legendary University of

Pennsylvania triumvirate of George Crumb, Richard Wernick, and George

Rochberg. He also studied with Karel Husa, Ralph Shapey, Henry Brant,

and, in his high school days, extensively with Elie Siegmeister. By

1985, he had become a full-time editor at music publisher Theodore

Presser Company. "The interesting ironic twist was that most of my

teachers, including Richard Wernick, Ralph Shapey, and George Rochberg,

are published by Presser. I was putting the red marks in the scores of

the very guys that were doing the same thing to my music as a

student." It's all the more remarkable that Dorff has been able to

guide his artistry through a particularly stormy period in musical

history and still emerge with his own voice fully intact. This is a

circumstance that the composer himself takes for granted, even as the

cardinal rule not to imitate one's teachers is often violated. In

many ways, Dorff's entire life has led, step by step, to his current

position in the world of music. He was a kid whose parents never had to

tell him to practice (he still plays bass clarinet and saxophone). He

taught himself basic harmony with Beatles fake books. As a teenager, he

and his friends played Stravinsky on the boom box at the beach. As for

his job at Presser, now vice president of publishing, he says that "I

think I was born to work there. As a child, I got into trouble for

correcting my teachers' grammar. I must have been really obnoxious." Maybe

a nicer way to say it is that Dorff has always possessed a firm

self-confidence, especially his conception of his personal voice. His

music has always been tonal, following such heroes as Copland, Ravel,

and Barber. When Dorff entered Penn, such material "was not taken too

seriously in academia. I was patted on the head, and told I didn't

have a voice yet. But it was the other students who didn't have a

voice. They all sounded like their teachers. Everyone worshiped either

the traditionally atonal

music of Elliott Carter or the eclectically atonal music of George

Crumb. But the avant-garde then was at least 20 years old, and wasn't

really avant-garde anymore." This

attitude was already well formed at this point in Dorff's creative

life. "When I was 17 and only composing for half a year, I went to the

Aspen Music Festival, surrounded by graduate-level composers from the

major conservatories who knew what was expected of them in 1973. Elliott

Carter came to our seminar class for a generous session of critiquing

everyone's work samples. I offered a movement I'd just written,

which, coincidentally, is the Ballade from Dances

and Canons on

the Perennials CD (track 21). Carter gave me a stern lecture on not

writing pretty melodies in 1973 in a world that has seen war atrocities,

saying I was living in Schubert's Vienna to be writing music like

that. I politely but confidently replied that Schubert lived a terrible

life of suffering whereas I was a spoiled bourgeois from Long Island,

and that following Carter's logic of necessarily depicting one's

world, I should be writing Schöne Müllerin and

Schubert should have composed atonal expressionism. My older and wiser

classmates gasped, but little by little I heard that many were shocked

that I dared to be honest. "Many

of my composition teachers commented that I was surprisingly honest in

my music. I don't understand why they found this surprising or rare. I

am expressing myself, not expressing them. That's why I do this as my

life's work-for my sake, not for other composers' prejudices. I

hope they're writing honestly, not trying to impress the media and

their colleagues. Why would anyone go into this career if it isn't out

of a self-contained vision? "A

few weeks later, Virgil Thomson heard the same Ballade that offended

Carter, and Thomson announced to the entire composers' seminar that

'young Dorff is the only talented one in the bunch.' Even at 17, I

knew that meant I was the only one with his aesthetics, and that

Thomson's praise was as meaningless as Carter's criticism. I always

asked teachers 'never mind about the style, is it a good piece?' and

it seemed like that was an impossible conundrum in the 1970s. I was

either a teacher's pet or else not taken seriously. It was about the

polemics of style, not the craft of composition." The

late Rochberg was an especially important mentor. "He told me a

wonderful story that had a profound effect on me. According to George,

when he was faculty advisor for the student composers' concerts at

Penn, a woman (whom he'd seen in the audience frequently) came up to

him and said 'Professor Rochberg, I come to all the student concerts,

and if your students were engineers, I wouldn't drive across their

bridges.' What a profound metaphor. I bet she'd drive across

Brahms's bridges, or Rochberg's, or Messiaen's. It's not about

the style, it's about building a musical structure. While I was a graduate

student at Penn, my sister was also there as an undergraduate in

architecture. One of the freshman assignments was to build a chair out

of corrugated cardboard that a 250-pound professor could sit on. To

pass, they had to figure out how to design the structure to make the

force of his weight support the chair's engineering. Just like putting

musical patterns together." Rochberg's

influence on Dorff continued after the elder composer's death; "Last

summer I was having trouble starting a flute sonata and wanted to

conceive a 20-minute, three-movement structure. I went to George's

grave in Valley Forge and let my imagination have a conversation with

him. The sonata started flowing wonderfully that night, and you could

drive a truck across it." After

grad school, Dorff took Crumb's advice to spend some time away from

academia. "I took an apartment in Center City [Philadelphia] to do

some freelance work and be alone with my imagination. Then, I think by

mistake, I was asked to write a musical for the sixth graders at the

Greenfield School. I'm pretty sure they had me confused with someone

else with a similar name who was already writing children's music. I

took the gig anyway, which was to set students' poems in a rock and

roll style. It was so refreshing to not be self-conscious and just

write. It opened up a dam, just as Crumb had predicted. I was thinking

phrase to phrase, rather than note to note." Thus

was born Dorff's unexpected career as one of the most performed

composers of children's music in the country. "I started to get a

reputation as someone who could write both seriously and tonal and be

genuine about it. The poet-in-residence at Young Audiences of

Philadelphia, Frank McQuilkin, was looking for someone to write an opera

with. Stone

Soup was

my first commission, and it ran for 21 seasons, which makes it the

longest running opera in Philadelphia history!" And on it goes;

Atlanta Opera is performing it about 50 times this season. Dorff's

ethos as a composer of children's music is to appeal on a number of

levels of sophistication, but not to lecture about the music, such as

Britten does in Young

Person's Guide to the Orchestra. His

1985 work for the Sacramento Symphony, Billy

and the Carnival, for example, features

every instrument in the orchestra, but no pedantry. "It has the big

smile points and catchy tunes, but goes deeper, just like Rocky

and Bullwinkle appeals to kids but has

hidden jokes for the grown-ups. It accidentally teaches about

orchestration." Dorff's

breakthrough came in 1996, when he responded to an open call for a

composition for mixed octet and narrator from the Minnesota Orchestra.

"I responded to a call for a new commission and won, leading to the

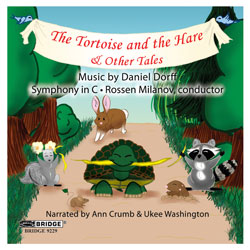

commission to compose 'Three Fun Fables,' from Aesop. The Aesop

stories are engaging, but the real moral of Three

Fun Fables is

that it's fun to go to classical music concerts. They have played it

over 100 times and also commissioned a follow-up, Goldilocks

and the Three Bears, which they have also

played over 100 times. I made an orchestral version of the 'Tortoise

and the Hare' segment, which we did with the Haddonfield Symphony [for

which Dorff is the current composer-in-residence] with [Olympic track

star] Carl Lewis as the narrator. The Philadelphia Orchestra then

commissioned me to complete the orchestration for the other two fables,

which Sawallisch premiered at a children's concert." That was in

2000, and since then the orchestra has performed his music on further

children's concerts and commissioned five more works for their Sound

All Around series. The

children's music continues to be produced, upon commission, at a

steady pace. One work of note is Blast

Off, which was underwritten by

Lockheed-Martin and premiered in Haddonfield with astronaut Kenneth

Reightler as narrator. Dorff asked the veteran space traveler if he was

nervous about the performance. His response; "Well, I've flown in

outer space many times, docked with the Mir, and I was on the shuttle

mission that supposedly had UFO sightings. I'd say today is a low risk

mission." Dorff has appreciated that unique perspective ever since. Dorff's

special engagement with children's music has taken place concurrently

with his unabated contributions to the "grown-up" repertoire. His

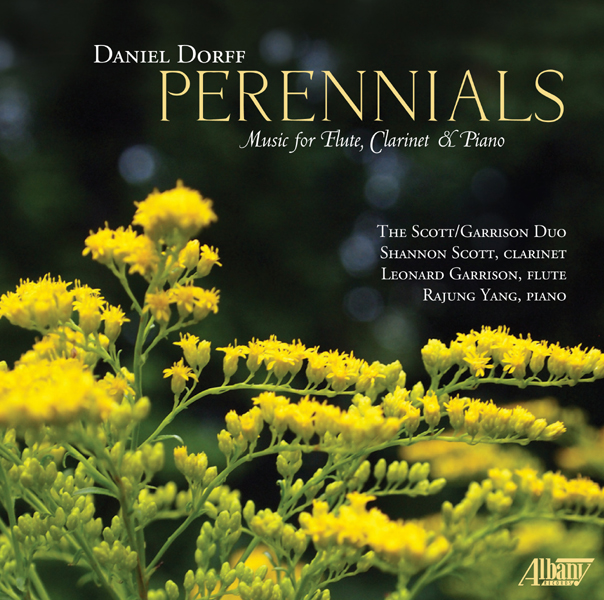

newest CD, Perennials,

is a wonderful showcase for his career to date. The music actually spans

his entire mature career, and displays a remarkable consistency in the

composer's way of creating music. As early as his experience in Aspen,

he was "creating repertoire rather than trying to make a bold

statement about music." That year, he won his first competition for

writing, and considers it significant that the judges were not

academics, as is often the case, but fellow musicians. "Musicians

really like playing my music out of genuine enjoyment, not because

it's the right thing to do. I have a few piccolo/piano recital pieces

that have become standard recital repertoire and are mandatory

selections at many competitions. Piccoloists play these because it's

music they want to play, not because it's new. "I

get commissions and prizes from performers, and not from new music

organizations who ironically and hypocritically think atonality is new

since it's been around for over 100 years. There have always been both

streams, and I went through decades of being told I'm not a composer

yet because I'm still using a key signature, and that Barber, Copland,

Rutter, and other neo-traditionalists don't really count." The

clear, honest and beautifully crafted esthetic of Dorff's music is a

crisp reflection of his goals as an artist. "I don't consider myself

naïve, and I have many friends and colleagues who are composers and

professors with a wide variety of musical languages, and my listening

tastes are wide-open. I love Beethoven and Brahms and wouldn't

consider writing like them because that's not my musical imagination.

Likewise, I love the music of Schoenberg, Messiaen, Crumb, and many

other recent modernists and I wouldn't consider writing like them

either, because that's not my musical imagination. I like to create

beauty and warmth in my own language, and that has nothing to do with

what year a piece is written in, just how it sounds. Music sounds how it

sounds, and chronology is irrelevant to the actual piece itself." The

music on this disc spans 36 years in the career of Daniel Dorff, from

1975 to 2011. So this is a retrospective, in a way, and yet there is a

remarkable consistency of style and quality in his writing. The core of

Dorff's influence, by his own admission, is the French tradition of

woodwind writing, which favors lyrical phrasing and natural pacing.

Dorff has studied with some of the most adventuresome composers of the

second half of the 20th century, including George Crumb, Richard Wernick,

George Rochberg and Ralph Shapey, but his own voice is unabashedly tonal

and accessible. Much of his material was specifically written for his

many musician friends. Dorff prides himself on creating musical material

that musicians really enjoy playing, and that shows in all of this

music, which is favored with delicious performances. Besides

the stimulus of the players, Dorff, who contributes the charming notes

for this release, also recounts some amusing circumstances that resulted

in the music on the program. Two

Cats, for example, was written for a

fundraiser for the Dutchess County, New York Society for the Prevention

of Cruelty to Animals, and is a witty dual portrait of a 20-pound tuxedo

cat and a petite Bengal. The Pastorale is

an ode to that ancient tradition of singing for one's supper; Dorff

wrote it as wedding music for a friend who regularly played at the piano

bar of a popular Philadelphia restaurant, Frög,

thus the subtitle, Souvenirs

du Frög. Interspersed

in this compelling mix are four elegant arrangements of Bach Inventions,

which introduce a nicely contrasting baroque texture to the essentially

Gallic sensibility. There

are no thunderbolts of innovation in this collection, but simply very

satisfying, beautifully crafted works, delectably performed. If you need

those thunderbolts, look elsewhere. If you think you might enjoy a rich

soufflé of wonderfully conceived and executed chamber music, dig in.

|

|